- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

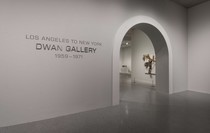

Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971, the first museum exhibition to chronicle the eleven-year run of Virginia Dwan’s bicoastal gallery, anticipates the promised gift of the art dealer’s collection to the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC. During a period of incredible transformation in American and European art, Dwan was at the forefront, mounting exhibitions that helped define trends as diverse as Pop, Minimalism, Conceptualism, and land art. Dwan innovated in other ways as well: she was the first American dealer to operate simultaneously a gallery on each coast, with locations in Los Angeles (1959–67) and New York (1965–71). Ironically enough for a show focusing on an art gallery, this was also the period when artists made galleries ostensibly irrelevant. Dwan was in the vanguard here, too, as the patron of earthworks such as Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970). As an heir to the 3M fortune, Dwan was able to take big risks. Sales were rare, a fact that became a joke among her gallery’s artists, whom Dwan supported with stipends and funds to fabricate their work. Thus Los Angeles to New York is less an exhibition about the 1960s art market than it is a testament to Dwan’s adventurous eye.

Dwan’s emergence as a dealer coincided with the expansion of air travel and the growth of the US interstate highway system. As exhibition curator James Meyer explains, this increase in the speed of travel helped Dwan foster “dialogues across regional and national lines” (26). The technological advances of the jet age did more than just allow the shipment of works of art for exhibition; we learn that early Dwan Gallery artists accepted Dwan’s invitation to stay in her Malibu guesthouse and work in a space nearby. For example, in making the combine Wooden Gallop (1962) for a show at Dwan, Robert Rauschenberg extended his practice of scavenging materials from the streets of lower Manhattan to the coast of California, where he found a rubber life raft and paddle while staying in Malibu. Arman came to Los Angeles from Paris and remained for three months, completing half the works he exhibited with Dwan that same year (47). Analysis of the post-studio practice encouraged by artists’ newfound mobility is a significant thread that runs throughout the exhibition.

The presentation in Washington featured just over one hundred artworks, including objects from Dwan’s collection and many others that were shown in or sold through the gallery. (The relationship of each object to the gallery was not made clear in the wall labels at the NGA, an issue corrected at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art [LACMA] exhibition.) Arranged chronologically, the show began with a nod to Dwan’s early interest in bringing New York School artists to the West Coast, displaying paintings by Franz Kline, Philip Guston, and Ad Reinhardt. Meyer argues that Reinhardt and another painter of monochromes, Yves Klein, forecast Dwan’s later interest in Minimal art (36). The two artists’ significance to Dwan is underscored by the presence of works by both in her collection, including a large black painting by Reinhardt, Abstract Painting A (1954), and works in different media by Klein.

The exhibition was at its best when it connected artists in surprising ways. A good example is the role Los Angeles artist Edward Kienholz played as an ambassador to visitors such as the French new realists. Portraits of Dwan by Jean Tinguely and Kienholz evoked jaunts to the city’s junk shops in search of artistic materials. Kienholz used an inverted crystal vase, an old aquarium, and the feet of a table in his Portrait of Virginia (1963), while Tinguely combined a circuit board, andiron, and other pieces of metal to evoke Dwan’s slender, feminine form in one of his signature motorized constructions dedicated to the dealer. Suggestive of the rapport between artists is Kienholz’s Traveling Art Show Kit (1961), an outmoded case containing everything Klein would need to make a monochrome: a spray can labeled “IKB,” another container labeled “GRIT,” a toothbrush, and a painter’s cloth. The luggage tag names the owner of the case, “Yves Klein,” and gives the address as “The Universe.”

We might expect Smithson to dominate an exhibition about Dwan Gallery, but for this viewer Kienholz emerged as the star of the show. At the NGA, his work occupied an entire room, with Back Seat Dodge ’38 (1964)—one of three tableaux included in his second solo exhibition with Dwan, in 1964—as its centerpiece. It was accompanied by two Conceptual works that helped Kienholz solve the problem of high fabrication costs associated with his tableaux by breaking down their realization into three distinct stages. The first (and the one with the highest price tag) was a framed description of the work, accompanied by a plaque engraved with its title. If Reinhardt and Klein point to Minimal art, then Kienholz provides a link from 1950s assemblage to the Conceptualism also supported by Dwan.

Group shows allowed Dwan and gallery director John Weber to posit historical precedents for the contemporary artists they exhibited and to broaden significantly the range of artists they engaged. Given its place within the annals of Pop, it was a shame the Dwan Gallery exhibition My Country ’Tis of Thee (November 15–December 15, 1962) was largely absent from the presentation at the NGA. Better represented were the four annual language exhibitions initiated by Language to be looked at and/or things to be read (June 3–28, 1967). These sprawling surveys charted the Conceptual turn as it unfolded, collectively featuring more than 180 works of art (77). The gallery given over to the language exhibitions in the Washington show was one of the few to highlight the work of women artists, including Eleanor Antin, Nancy Holt, Rosemarie Castoro, and Lee Lozano, and served as a reminder that, despite mounting early solo exhibitions by Joan Mitchell (1961) and Niki de Saint Phalle (1964), Dwan was no different than her peers in filling her gallery roster with white men (385).

Perhaps the most storied group exhibition to be mounted at Dwan Gallery was 10 (October 4–29, 1966), a show that Meyer describes as “something of a manifesto” for Dwan, who promoted in it the aesthetic that would come to be called Minimalism (72). One of the handsomest rooms at the NGA approximated the show’s list of participating artists, mainly with works drawn from Dwan’s personal collection. As Meyer points out, the artists who gathered in Dwan’s New York apartment to discuss the show—Reinhardt, Sol LeWitt, Smithson, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, Agnes Martin, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Jo Baer, and Michael Steiner—were “gifted polemicists” who rarely agreed (70). Unable to come to a consensus on a title for the exhibition, they settled on their number, ten. One of the opportunities Los Angeles to New York afforded viewers was, in representing the messiness of art’s history, allowing them to see how trends now codified looked to participants on the ground. The curatorial decision at LACMA to carve three large rooms out of a cavernous exhibition space in the Resnick Pavilion and to label them with the names of artistic trends, including Minimal art, worked against this possibility. A survey as large as Los Angeles to New York could easily devolve into incoherence, and Meyer has done an admirable job of presenting the Dwan Gallery’s history as a compelling narrative—but there is also a danger in telling this story too neatly.

Each exhibition venue included an example of the large-scale sculpture Dwan promoted. In Washington, Mark di Suvero’s Pre-Columbian (1965/2004), a rotating assemblage of metal, wood, and an old tire, tempted viewers to give it a spin. In Los Angeles, Robert Grosvenor’s Untitled (yellow) (1966/2016) dramatically plunged down from the ceiling and hovered just above the floor. Notably, by the end of the 1960s, Dwan and her artists had moved farther afield from the gallery—and from Los Angeles and New York—to the western deserts. Here the same types of earthmoving equipment that had built the interstate highway system became, with Dwan’s support, tools for making art. Neither exhibition venue offered any new solutions to the problem of exhibiting land art, though at LACMA the juxtaposition of Smithson’s Gyrostasis (1967) with Heizer’s Levitated Mass (2012)—a 340-ton boulder sited behind the Resnick Pavilion and visible through a window wall—was a happy coincidence.

The catalogue for Los Angeles to New York follows the model of the artist’s monograph but with an art dealer as its focus. It features a chronology of Dwan’s activities, previously unpublished writings, and a detailed exhibition history of Dwan Gallery. The inclusion of exhibition checklists and reviews makes excellent use of the Dwan Gallery archives and should prove useful as a research tool. Beyond the catalogue, it is worth visiting the NGA’s website for podcasts of lectures given in conjunction with the exhibition, a recorded conversation between Dwan and Meyer, and a film produced in support of the show.

Amanda Douberley

Academic Liaison/Assistant Curator, William Benton Museum of Art