- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

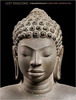

In spring 2014, the Metropolitan Museum of Art presented a groundbreaking exhibition of early Hindu and Buddhist artworks from Southeast Asia. Aptly titled Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, the exhibition brought together treasures from nearly thirty institutions and collections across nine different countries, many of which had never before traveled outside their country of origin. Carefully grouped, juxtaposed, and emplaced in the Metropolitan’s galleries, the artworks revealed striking similarities and intriguing departures from Indian prototypes. Examining long-distance networks, regional developments, and local adaptations, Lost Kingdoms sought new ways of understanding how, and why, Indian ideas and images reached Southeast Asia, and how, and why, they transformed and gained meaning upon entering the region.

Lost Kingdoms represents a watershed moment in the historiography of Southeast Asian art, especially in terms of its relationship with India. As John Guy, the Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia at the Metropolitan Museum and curator of the exhibition, outlines in his introductory essay for the exhibition catalogue, Southeast Asia was first understood through paradigms of colonialism, most notably established under French epigraphist George Coedès in the 1930s and 1940s, as a way to justify French activities in the region. Turning away from this historically determined model, in which Southeast Asia was cast as the passive recipient of Indic traditions, beginning in the 1970s scholars sought to redefine the artistic tradition of Southeast Asia—itself diverse and dynamic—independently of India. Focusing on vernacular arts, this second paradigm left little room for the Hindu-Buddhist masterpieces of Lost Kingdoms. The field is now in need of a third paradigm, one in which India’s role is neither overemphasized nor dismissed in the formative history of Southeast Asia’s religious art. Proposing a model of selective adaptation, reconfiguration, and intelligent incorporation, Lost Kingdoms and its accompanying catalogue begin to do this work.

The catalogue is organized into five thematic sections that convey the exhibition’s principal narratives: the importation and integration of Indian religions; the role of Brahmanical cults (dedicated to Viṣṇu, Śiva, and associated deities); the rise of Buddhist art as an expression of state identity; and the development of savior cults (dedicated to the bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Maitreya). Each section includes a selection of essays by various specialists, followed by relevant catalogue entries written by Guy. Relatively short essays allow for contributions by many of the leading experts in Southeast Asian sculpture, archaeology, and epigraphy, with topics ranging from iconography and religion to technical analysis. Chronologically, the scope begins with the fifth century, the period when the first large-scale stone sculptures of Indian deities were created in Southeast Asia and when a written record of Brahmanical rituals emerged in the region. It concludes at the close of the eighth century, when the tightly knit regional kingdoms of this formative period gave way to expanded networks of maritime trade. Beautifully illustrated with full-color images, the catalogue, like the exhibition, serves both as an aesthetic indulgence and an important scholarly resource for a wide range of specialist and non-specialist audiences.

Preceded by three useful maps that show the little-known find spots of the objects on view, the catalogue’s first section, by Guy, introduces the cultures and kingdoms of early Southeast Asia and positions them within broader networks of trade, politics, and pilgrimage. Bérénice Bellina’s essay establishes the cultural complexity of early trading polities in Southeast Asia through archaeological means. Geoff Wade draws attention to the importance of Chinese textual sources in illuminating Southeast Asia’s early Hindu-Buddhist history. Archaeological research and the Chinese literature both continue to serve as important evidence throughout the volume. The catalogue for this section includes Indian prototypes (cat. 10) and informative examples imported to Southeast Asia through maritime networks; it also includes artworks that reveal the early incorporation of Indic imagery and ideas into the region, as well as a receptivity for imagery associated with nature.

The emergence of Indian traditions in Southeast Asia can be traced not only through visual imagery and the transfer of materials, but also through epigraphic content and the development of local scripts. In the second section, Arlo Griffiths tracks the very idea of writing to India. Considering ritual and legal texts inscribed on stone, metal, and terra cotta, Griffiths draws attention to the transformations that took place when Indic languages and scripts were incorporated in Southeast Asia. Peter Skilling looks at the dissemination of the Stanza of Causation (Ye Dharmā), citation inscriptions, and textual configurations unique to Southeast Asia written in Sanskrit and Pali across the Buddhist world. The next two essays turn to evidence from Myanmar and Champa (southern Vietnam) to address the formation of early urban centers and the role of inscriptions in elucidating the Buddhist histories of these areas. Through their recent archaeological research, U Thein Lwin, U Win Kyaing, and Janice Stargardt historicize the ancient city of Śrī Kṣetra (second-century BCE to ninth-century CE) and discuss the great many inscriptions and artworks from this Pyu site. Pierre Baptiste turns to the earliest artistic and epigraphic remains from Champa. Buddhas, primarily from Myanmar and southern Vietnam, and inscribed objects and sculptures comprise most of the catalogue for this section. Included is an inscribed stele from Malaysia, circa sixth century (cat. 19), which constitutes the earliest epigraphic evidence of Buddhist practice in the region, and four monumental seated Buddhas (cats. 41–43, 47) that exemplify the diverse ways in which Indic models were subtly transformed and made local.

Brahmanical cults in Southeast Asia played a crucial—and comparatively less studied—role in the region. Although Guy expresses his regret that he was unable to accept loans from Indonesia due to budgetary constraints, two essays (and a group of objects at the end of the catalogue) allow for the inclusion of this important center of Hindu-Buddhist activity. Pierre-Yves Manguin’s extensive archaeological research in Srivijaya and also Funan has exposed a complex network of polities that lay at the epicenter of long-distance trade. Agustijanto Indradjaya looks at the scope of Hindu-Buddhism in early Indonesia, not only in Java and Bali, but in the more remote islands of Kalimantan and Bima. The next two essays are more traditionally art historical, tracing the trends and transformations of stylistic elements chronologically. Le Thi Lien focuses on Hindu and Buddhist style in sculptures from southern Vietnam during the period in which Funan flourished. Hiram Woodward begins with Cambodia and looks across mainland Southeast Asia to consider more widespread trends in decorative motifs and sculpture. As he demonstrates, makara mouths may have become vegetal abstractions, but the process was neither consistent nor linear. Woodward’s concluding remarks on the eighth century set the stage for the remainder of the period of study, when Mahayana Buddhism became the dominating force in Southeast Asia. The catalogue for this section includes many masterpiece sculptures, such as the exceptional standing Viṣṇu from Phnom Kulen (cat. 79), Viṣṇu’s avatars Kṛṣṇa Govardhana and Kalkin (cats. 73–74), superb figures of Śiva and the mysterious Aiyanār (cat. 103), liṅgas, goddesses, and members of the Śaiva pantheon.

Although Brahmanical deities were associated with the fashioning of kingship, it was Buddhism that would come to dominate statehood in Southeast Asia. The fourth section turns to the construction of state identities through sponsorship of the Buddhist communities discussed in section 2. The essays center on Thailand. Robert L. Brown and Thierry Zéphir focus on the symbol of the Wheel (cakra) and its emergence as emblem of the Dvārāvatī state. Through the study of sema stones (boundary markers), Stephen A. Murphy demonstrates the importance of Buddhist monasteries in religious and urban life in early northeastern Thailand. The catalogue includes impressive figures of the Buddha in acts of meditation, preaching, or enacting miracles, as well as a number of monumental, yet intricately carved, Dharmacakras (Wheels of the Law) (cats. 122–23).

The final section is dedicated to the savior cults that became prominent in the eighth and ninth centuries. Centered on the bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Maitreya, these cults received substantial patronage from wealthy merchant communities that traveled across the maritime networks. Arguing for cosmopolitanism, Pattaratorn Chirapravati highlights the concurrent presence of Buddhist and Brahmanical communities in Si Thep, Central Thailand, and the role of Surya as a potential bridge between the two streams of practice. The catalogue is replete with ethereal bronze statues, such as the expertly cast bodhisattvas from Prasat Hin Khai Plai Bat II (cats. 139–42). Dating to the eighth/ninth centuries, the final group of sculptures reflects the close contact between northeastern India and Southeast Asia that gave rise to tantra in the region.

The publication is completed with appendices on stone types, sculptural practices, and technical analysis of bronze-casting techniques, authored by leading conservation scientists in the field Federico Carò and Janet G. Douglas, and Lawrence Becker, Donna Strahan, and Ariel O’Connor. Then follows an extensive bibliography and a glossary of sites in first-millennium Southeast Asia.

“The adaptation of Indic culture in Southeast Asia was a process of continuous dialogue and reinvention,” writes Guy in the introduction (4). It is somewhat surprising, therefore, to find in several essays a persistent and uncritical use of antiquated terms such as “influence” and even “Indianization.” Nevertheless, Lost Kingdoms presents a truly remarkable body of material that will enable scholars to continue working toward new ways of understanding and articulating the interactions between India and Southeast Asia in the Hindu-Buddhist period. The publication will be of great use to scholars and collectors, and of interest to more general audiences. As an exhibition, Lost Kingdoms brought an exquisite selection of artworks into public view and into dialogue with each other for a limited amount of time. The well-researched and beautifully illustrated catalogue enables these conversations to continue.

Emma Natalya Stein

Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow for Southeast Asian Art, Freer|Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution