- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Leonardo da Vinci: Hand of the Genius, organized by Atlanta’s High Museum of Art in collaboration with the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, and the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore and Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, Italy, aims to explore an aspect of Leonardo’s wide-ranging interests long acknowledged but still poorly understood. That Leonardo studied from, theorized on, and made designs for sculpture has been established through his drawings and writings yet is frustratingly absent in surviving works. This small but rich exhibition aims to bridge this gap by displaying well-known drawings alongside three-dimensional works by mentors, colleagues, and students. The extraordinary loans of several recently cleaned sculptures by Donatello, Andrea del Verrocchio, and Giovan Francesco Rustici celebrate another series of spectacular conservation campaigns by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure and offer a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to explore Leonardo’s relationship with three-dimensional form through beautiful pairings of related drawings and sculptures.

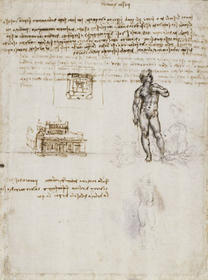

In Atlanta, the exhibition filled six thematically organized galleries with forty-eight works, including twenty-four drawings by Leonardo. The show opened with five studies in various media of horses and equestrians (pls. 26, 29, 31, 33, and 34) and an engraving after four other sketches (pl. 9) spanning the almost forty years that Leonardo explored and reworked equestrian projects. The exhibition then considered Leonardo’s study of antiquity and its specific application to these projects with several sheets filled with notes and sketches of horses, machinery, and a profile of Nero (pls. 22 and 27), nicely paired with two first-century bronze coins showing rearing horses and the emperor (pls. 6 and 7) and two Hellenistic miniature bronze horses (pls. 4 and 5). Such exploration complemented Leonardo’s investigations of how to cast a large equestrian monument, exemplified by three measured drawings of horses after Leonardo from the Codex Huygens (pls. 23–25) and a sheet recording Leonardo’s ideas and notes for the Sforza casting (pl. 30), which have been usefully enlarged and translated on accompanying wall charts.

The show then focused on Leonardo as a student of sculpture with marvelous pairings of works by mentors with related drawings by Leonardo, such as Donatello’s marble Bearded Prophet (ca. 1418–20) from the east side of the Campanile (pl. 2) with a series of drapery and figure studies (pls. 1, 3, 11); Desiderio da Settignano’s charming marble Christ Child (ca. 1455–60; pl. 12) with Leonardo’s equally tender red-chalk Bust of a Child in Profile (ca. 1495; pl.13); the marble Alexander the Great (ca. 1483–85) from Verrocchio’s workshop (pl. 19) with Leonardo’s related pen-and-wash sketches of armor and dragons (pl. 20); and the pair of terracotta Flying Angels (1470s) from Verrocchio’s workshop now in the Louvre (pls. 16 and 17) with Leonardo’s Study of a Winged Figure, an Allegory of Fortune (ca. 1481; pl. 18). Curator Gary Radke proposes that the left-facing angel was possibly sculpted by Leonardo himself (pl. 17, 40–43), an attribution difficult to sustain without any secure points of comparison in Leonardo’s oeuvre or a clear understanding of how Verrocchio delegated tasks among his assistants and apprentices.

Radke also finds Leonardo at work alongside Verrocchio in the glorious silver relief showing the Beheading of St. John the Baptist (1477–78) from the recently restored altar of the Florentine Baptistery (pl. 21). Seeing differences of expressive content, modeling, and surface detail, Radke proposes Leonardo as responsible for the youth with a salver at the composition’s far left and the turbaned officer shown from behind at the right (49–58). It seems more likely, however, that these differences result from the figures’ greater salience when viewed in situ from above at an angle rather than because of the presence of three independent artists at work, as Radke proposes. Regardless of how Verrocchio may have divided labor in his workshop, the relief’s newly cleaned surface is magnificent, and the exhibition offered viewers a rare chance to inspect it at close range.

The exhibition continued with a section on Leonardo’s relationship to Michelangelo through exploration of his designs for a Hercules of ca. 1508 to stand opposite the latter’s marble David (1504) in the Piazza della Signoria (pl. 37) and his abandoned Battle of Anghiari mural (1503–06) intended to mirror Michelangelo inside the governors’ palace (pls. 45 and 46). Once again, Leonardo’s study of and influence on other sculptors is made clear through inclusion of battle reliefs and figure groups by Bertoldo di Giovanni (pl. 48), Lorenzo Naldini? (pl. 49), Willem Danielsz. van Tetrode (pl. 44), and Rustici (pls. 41 and 42), as well as the much-debated Budapest Horse (pl. 43), given here with hesitation to Leonardo himself. The copy after Leonardo showing The Fight for the Standard of the Battle of Anghiari, famously reworked by Peter Paul Rubens (ca. 1615; pl. 47), further suggests the power, grandeur, and excitement of Leonardo’s failed mural, which so captivated the imaginations of sculptors like Rustici and Danielsz.

These vigorous battle scenes were followed by a small section devoted to studies of anatomy and facial expression and their application in works like the unfinished Vatican St. Jerome (ca. 1480; pl. 36). The exhibition concludes with the stunning display of Rustici’s monumental bronzes for the Florentine Baptistery depicting St. John the Baptist Preaching to a Levite and Pharisee (1506–11; pl. 35). Beautifully conserved, the figures stand as a testament to Rustici’s skill and allow a glimpse of Leonardo working in three dimensions, if Vasari’s claim, cited in the exhibition catalogue, that “Leonardo worked at the group with his own hand, or . . . at the least assisted Rustici with counsel and good judgment” (162) can be believed. Given Vasari’s use of Leonardo as the founding father of the Renaissance’s “third age,” as well as Leonardo’s failures with his own sculptural commissions, it seems that “counsel and good judgment” are all that should be assigned to him, reserving primary accolades for Rustici himself.

The accompanying publication provides a collection of essays exploring various aspects of Leonardo’s three-dimensional thinking as well as a DVD-ROM with three short documentaries on the history of the cathedral complex, Rustici’s figural group, and its recent conservation. In “Leonardo, Student of Sculpture,” Radke deals with Leonardo’s early sculptural experiences, offering intriguing if ultimately unconvincing attributions of Verrocchio-workshop productions to Leonardo himself. In “What is Good about Sculpture?” Martin Kemp tries to resolve Leonardo’s paradoxical relationship with sculpture, as the artist was clearly “one of the greatest visualizers of forms and space in three dimensions” (63) who nevertheless famously excoriated the sculptor’s art in his Treatise on Painting, a collection of his ideas gathered posthumously by his pupil Francesco Melzi. Kemp sees the latter as rhetorical exaggeration resulting from courtly debates on the arts and the artist’s own failures as a sculptor rather than a rejection of the artistic possibilities of three-dimensional form. Pietro C. Marani proposes the famous Vitruvian Man sketch (ca. 1492; Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, 228; fig. 51) to be an introductory illustration for a never-completed treatise on sculpture, while Andrea Bernardoni offers a meticulous reconstruction of Leonardo’s casting technique for the ill-fated Sforza Horse, illustrated with twenty-three highly illuminating reconstruction drawings, to conclude that Leonardo’s casting mold would have ultimately failed. A re-creation of the Sforza Horse made in polystyrene resin by the Opera Laboratori Fiorentini was on view in the main piazza of the High Museum, allowing viewers to appreciate the audacious scale on which Leonardo hoped to honor Francesco Sforza (pl. 32). In “An Abiding Obsession: Leonardo’s Equestrian Projects, 1507–1519,” Radke and his former student Darin J. Stine provide a painstaking reconstruction of the Trivulzio monument based on a new reading of Leonardo’s estimate for the project, translated in an appendix, and speculate on a series of drawings first recognized by Martin Clayton to be for an undocumented equestrian project for King Francis I (pl. 34). Philippe Sénéchal explores the relationship between Rustici and Leonardo, finding him at once highly indebted to, yet often radically departing from, the example of his friend and mentor, concluding Rustici to be “one of the most inventive artists of the first half of the sixteenth century and one of the fathers of Florentine anticlassicism” (193). Using records (transcribed in an appendix) from the Florentine public foundry known as the Sapienza, Tommaso Mozzati investigates the relationship between commissions for monumental bronze sculpture, Leonardo’s investigations of casting techniques, and the Florentine arms industry that led to “a radical redefinition of bronze” in the first decade of the sixteenth century.

While these essays do much to explore the topic of Leonardo’s relationship with sculpture, bronze casting, and three-dimensional thinking, the traditional apparatus of a catalogue, even simply a list of previous exhibitions for each work and an index, is sorely missing. Works included in the exhibition are indicated only by plates scattered throughout the text, rendering it a complement to, rather than record of, the exhibition itself. The DVD, produced by Friends of Florence, provides a useful tool for classroom instruction, offering a clearer understanding of the experience and importance of the cathedral complex and Rustici’s contribution to it. The section on the group’s conservation is especially illuminating for those unfamiliar with current restoration techniques.

A reduced version of the show, including all of the Windsor drawings; the Donatello, Verrocchio, and Rustici sculptures from Florence; the Rustici terracotta group from the Louvre; the Budapest bronze horse and studies of horse’s legs; and the Vatican St. Jerome, is on view in Los Angeles under the title Leonardo da Vinci and the Art of Sculpture: Inspiration and Invention. The Getty exhibition includes a double-sided sheet showing a Study for Hercules Holding a Club in front (recto) and rear (verso) views from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a key example of Leonardo’s sculptural thinking missed in the Atlanta exhibition (fig. 102). Whether in Atlanta or Los Angeles, Leonardo da Vinci and the Art of Sculpture is sure to raise anew interest in what Leonardo learned as an apprentice to sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio and carried with him throughout his fascinating, if at times frustrating, career, showing him to be a great sculptural thinker, if not a great sculptor.

Anne Leader

Editor, IASblog, Italian Art Society