- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

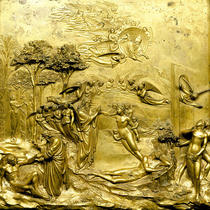

Two weeks after opening its Gates of Paradise exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum of Art held a symposium to explore various issues surrounding the creation, reception, and conservation of Ghiberti’s masterpiece. An international panel of art historians, curators, and conservators offered a range of general and specialist talks to accompany the remarkable loan of three narrative reliefs and four framing elements from the final set of bronze doors created for the Florentine Baptistery.

Ian Wardropper, Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Chairman of the Metropolitan’s Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts (ESDA), welcomed conference attendees. Cristina Acidini, Superintendent of the Polo Museale Fiorentino and the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, provided a brief institutional history of the Opificio and an overview of its conservation practices. James David Draper, Henry R. Kravis Curator, ESDA, introduced each speaker. All three praised the extraordinary nature of the collaborative exhibition; expressed gratitude for support of the twenty-five year conservation effort; thanked the Polo Museale for allowing these works to travel to Atlanta, Chicago, New York, and Seattle on their first and last visit to the United States; and emphasized how the exhibition, catalogue, and symposium provided important dialogue between art historians and conservators.

The exhibition’s organizer, Gary Radke of Syracuse University and the High Museum of Art, began the morning session with a review of his catalogue essay, “Lorenzo Ghiberti, Master Collaborator.” Radke was engaging in his description of Ghiberti’s workshop and the many interrelationships forged with other sculptors, painters, and architects. He emphasized Ghiberti’s adeptness at partnership and organization, which derived not only from his artistic skill but also from a charismatic and amiable personality that allowed the artist to work with a wide variety of patrons, co-workers, and assistants. Radke discussed Ghiberti’s numerous projects beyond the two sets of bronze doors, including his work on the cathedral’s dome and stained-glass windows—the frame he designed for the Linaiuoli guild’s altarpiece painted by Fra Angelico. Radke noted that Ghiberti’s collaborations were often by default, not simply by intention, and that competition was viewed as the means to arrive at the best design solution.

In his paper, “Documenting the Gates,” Rolf Bagemihl of the Accademia Italiana reviewed his historiography of the commission’s documentary evidence, which he first undertook for the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Ghiberti Workshop held in Florence in February 2006 and shared with Margaret Haines and Francesco Caglioti for their similarly titled catalogue chapter. The documentary history of the Gates was first explored in the seventeenth century, and much of our understanding comes from records preserved in copies, summaries, and notes made by the antiquarian Carlo Strozzi, which provide a valuable basis for understanding the historical circumstances of the commission. Information can also be gleaned from surviving Calimala guild records, Ghiberti’s tax returns and property records, as well as from the unused iconographical scheme proposed by Leonardo Bruni (also known to us through Strozzi). Bagemihl concluded that the transcriptions and three-phase chronology first published by Richard Krautheimer remain essentially valid with a few important changes, detailed by Caglioti in the catalogue: (1) 1424 to 1437 saw Ghiberti’s January 1425 agreement with the guild and the casting of all ten panels and the frame’s figural elements; (2) 1437 to 1448 saw the cleaning and chasing of the narratives as well as casting of the giant doorframes; and (3) 1448 to 1452 saw the completion of the decorative elements, gilding, and installation. We can now put aside Krautheimer’s theory of an intermediate design stage calling for twenty-four figural panels, recognizing that Ghiberti cast each door in one piece, with twelve blank squares on the back and five large fields for the narratives on the front.

Keith Christiansen, Jayne Wrightsman Curator from the Metropolitan’s Department of European Paintings, gave a brilliant lecture with the deceptively simple title, “Ghiberti and Painting.” Christiansen demonstrated the clear importance of Ghiberti for the early Italian Renaissance, finally putting to rest old biases against the artist that he was transitional, “Gothic,” or secondary to Donatello. Indeed, the collective theme of the symposium and corresponding exhibition catalogue challenges the standard refrain that Ghiberti was an essentially Gothic and conservative artist, and thus a transitional figure. Christiansen demonstrated the numerous ways that Ghiberti affected his fellow painters and gave concrete visual evidence to support the sculptor’s claim that he regularly made designs for his colleagues. In addition to numerous visual correspondences between Fra Angelico and Ghiberti, Christiansen elucidated important relationships with Pesellino and Fra Filippo Lippi. His thorough comparative analysis of the 1401 Sacrifice of Isaac competition panels elucidated Ghiberti’s narrative fluency and idealized beauty, making clear why he won the commission. Christiansen concluded with the claim that Ghiberti as much as Donatello should be regarded as indispensable to our understanding of the early Renaissance. If published, Christiansen’s talk would be essential reading for any student of the Quattrocento.

The morning session concluded with “Ghiberti, Perspective, and Vision” by Amy Bloch of the State University of New York at Albany. Focusing on various details from the competition panel and the doors, Bloch illuminated Ghiberti’s talents as a thoughtful narrator who used naturalistic details to enhance the emotional impact of his stories. Whether showing Abraham extending his finger to steady his blade as he contemplates plunging it into his son’s neck or manipulating his perspective grid to enhance narrative impact, Ghiberti continually questioned his compositional structures to ensure maximum legibility and narrative efficacy. Bloch convincingly argued that the larger format of the Gates of Paradise allowed the artist to explore the possibilities of linear perspective, showing him to be among the group of artists enthralled by Brunelleschi’s first experiments with spatial illusion. In a masterful formal analysis of Jacob and Esau, Bloch demonstrated how Ghiberti effectively manipulated his perspective grid by slowing, stopping, and interrupting the diminution of space with variously spaced transverse lines masked by narrative elements like Esau’s bow or his dogs. Despite these different perspective systems, the result is a deep, believable, atmospheric space effectively filled by a continuous narrative that moves from back to front and side to side. Such subtle adjustments allowed Ghiberti to use spatial illusion to his advantage rather than become a slave to its rules. One of Bloch’s most compelling suggestions was that Ghiberti’s placement of figures deliberately implies memories of past events between Esau and Jacob. This reading provides a heretofore unrecognized explanation of the foreground and middle-ground pairings of Esau’s humiliation with his selling of his birthright at the center or the coupling of Isaac’s deception with Rebecca’s conspiracy on the right.

The afternoon session turned to issues of conservation. Annamaria Giusti, Chief Curator, Department of Bronze Sculpture Conservation at the Opificio, reviewed her catalogue essay about the doors’ state of preservation in her “Conservation of the Porta del Paradiso: Experiences and Advancement in Knowledge.” She recounted the trials and tribulations of restoring such a complex and massive work, which took almost as long to clean as to make. The restoration revealed much about Ghiberti’s working methods, including the precision with which Ghiberti inserted the ten narrative and forty-eight framing reliefs, numerous repairs and alterations made as he worked, and the surprising discovery that forty coin designs for the Florentine mint were tested during the door frames’ casting. Giusti reviewed the cleanings, stresses, and damage sustained over the centuries and emphasized the most serious threat of unstable oxides beneath the gilding that threaten to corrode and destroy the gilt surface if exposed to oxygen. Despite these travails, the doors remain in remarkably good condition, now visible after their painstaking cleaning with infrared lasers and chemical treatments.

Richard Stone, Senior Museum Conservator of the Metropolitan’s Department of Objects Conservation, hypothesized how Ghiberti planned and executed the reliefs. The main dispute (reflected in two opposing catalogue entries) rests on whether Ghiberti employed a direct or indirect lost-wax casting technique. In contrast to his Italian colleagues, Stone and his collaborators make a strong case that Ghiberti used the direct method, translating the original wax model, which was lost in the process, into a unique cast. Relying on his deep knowledge of materials and techniques as well as on a close inspection of the reliefs themselves, Stone convincingly reconstructed how Ghiberti built and cast his panels, speculating that he used tracing paper and full-size drawings to create his wax models, thereby maintaining control over his designs even as workshop assistants participated in the monumental task of designing and casting the doors.

Edilberto Formigli, of the University of Siena and the Antiche Tecniche Artigianali, Murlo, reviewed his catalogue chapter exploring Ghiberti’s sophisticated chasing techniques, derived from his work as a goldsmith, and his coordination of the many assistants responsible for hammering, carving, refining, and polishing the cast bronze. Much of the decorative detail was absent from the wax models; rather, it was formed with a variety of punches and hammers in a cold-working of the bronze, whose finely tooled gilt surfaces have been revealed through cleaning. Formigli explained and illustrated the types of tools created and used by Ghiberti, including hammers and planishing punches for smoothing, flattening, and closing irregularities; tracer punches for lines, curves, and edges; and a variety of pattern-ended punches for decorative motifs. Formigli identified numerous pattern tools used on the reliefs, including three different circles, five rosettes, a star, and a half-moon. After painstaking chasing, the surfaces were gilded with the mercury amalgam technique, which required considerable smoothing and polishing to achieve the desired shine. Comparison of punchwork in all ten panels allows for speculation on where Ghiberti’s assistants—including Tommaso and Vittore Ghiberti, Michelozzo, Bernardo Cennini, and Benozzo Gozzoli—worked as they helped finish the surface articulation of the door’s panels and framing elements.

A. Victor Coonin of Rhodes College discussed the elaborate frame created for the south door of the Baptistery, a project led by Lorenzo’s son Vittorio, probably after designs by his father. Through close visual analysis, Coonin demonstrated that the frames of the north and east doors are quite consistent in design. He finds the south frame to be fundamentally different, with its classical bead-and-reel borders filled with a profusion of figural and floral decoration of great plasticity, and with distinct and separate transitions from one area to another rather than the seamless and unified flow between elements found in the other two frames. These differences led Coonin to identify Vittorio as head of the Ghiberti workshop after his father’s death. Coonin convincingly argued for the participation of the Rossellino brothers and Desiderio da Settignano in the south frame, crediting Bernardo with the fine classical moldings that do not have precedent in Lorenzo Ghiberti’s work. Coonin also reflected on Vasari’s mention of a model to replace Andrea Pisano’s doors and postulated that the south frame was a prelude to such a substitution, a scenario that seems highly unlikely considering the cost of replacement and the pride and satisfaction associated with Andrea’s original doors.

Andrew Butterfield concluded the symposium with a reflection on Ghiberti’s place in the history of early Renaissance sculpture. He correctly asserted that the restoration, exhibition, catalogue, and symposium will permanently change our understanding of the artist and his impact and force us to abandon the interpretations of John Pope-Hennessy, Krautheimer, and Ernst Gombrich who saw Ghiberti as a “Gothic” and uninventive artist. Butterfield was careful to acknowledge that we are not smarter than the pioneering art historians of the twentieth century, but rather emphasized how difficult it has been to evaluate and modify the entrenched narrative of the early Renaissance, which dates back to Vasari. With stunning new photographs by Antonio Quattrone, Butterfield reminded the audience once again of Ghiberti’s innovative naturalism, classicism, and narrative complexity. Leon Battista Alberti recognized Ghiberti’s importance in the revival of the arts, naming him and Brunelleschi, Donatello, Luca della Robbia, and Masaccio as the leading artists of the early Florentine Renaissance; it seems, at last, that we have, as well.

[To read Anne Leader’s review of the exhibition, click here.]

Anne Leader

Editor, IASblog, Italian Art Society